The Heroes that Get In Our Way

Why seeing a cape and mask is easier than seeing the human underneath

Photo by Limor Zellermayer on Unsplash

Superheroes are comforting.

It would be nice to have an impervious figure standing between us and our problems, always able to do more than we could and save the world in the nick of time. But after the Marvel insignia flashes on the screen and we chuckle at the final post-credit clip, we are returned to a reality where there are no super powers (probably, anyway).

Lacking gamma-ray induced powers, we nurture stories about the seemingly superhuman lives of certain people, usually in two categories:

Figures that overcame incredible circumstances to persevere and fight for what they believe in - think Malala, MLK Jr., Nelson Mandela, or Gandhi

Those we perceive as charismatic or enormously successful at something we value - like billionaires (Jobs, Bezos, and Musk), celebrities (Beyoncé or the Kardashians), and even cult leaders (or those with traits of all 3, like the original founder of WeWork, Adam Neumann for a time)

The former group is more likely to have respect from a wider audience while the latter is more likely to be labeled “controversial,” but both have some base of fans who idolize them as heroes.

The Fault in our Hero Worship

Meeting our heroes is risky. Finding flaws can shatter the aspirational place in which we hold them, and celebrated public figures are just as human as anyone else.

The true story behind the shiny persona is always human, which is to say contradictory and flawed (many historical heroes, like Winston Churchill, Gandhi, and many others held deeply racist beliefs, for example). Being human does not excuse the faults, but the presence of both virtue and scandal feels like uncomfortable mental dissonance to fans and critics alike.

We witness this moral ambivalence frequently with celebrities and billionaires, whose hype includes loud critics in addition to the fandom. As a year, 2020 provided ample fodder for identifying the flaws of the rich and famous, like Kim Kardashian tweeting about a brief return to “normalcy” from a private island birthday party for herself or billionaires ignoring privileged pasts to promote a “self-made” myth.

Despite visibility into their flaws, we want to believe the capabilities of our heroes are nearly superhuman, which requires us to actively deny their humanity.

Why Remove the Humanity?

Conceptually, we understand that famous figures are just people like anyone else, but we cling to the myths and stories of these personas.

Perhaps we don’t want to detract from a legacy we admire by admitting the pieces that are not so shiny. We want to defend our mental image of them and not provide fuel for critics. Maybe we are influenced by cultural opinions and the loudest media voices. Or we could feel defensive about a lifestyle that we may want even if we don’t have it now.

In the case of the “self-made” rags to riches stories, we find comfort in indulging a narrative we want to believe - that any one person can, through sheer grit and willpower alone, achieve any level of success. If we think people who are successful deserve it, we can believe in meritocracy. That enables us to believe we will succeed by being “good,” and that those who haven’t succeeded must not be “good.” From that point, it’s easy to write off uncomfortable issues like homelessness and poverty as a problem created by those experiencing it, while turning a blind eye to the systemic advantages of the privileged (at least until the scandal breaks like the college admissions bribery scandal of last year).

Avoiding the humanity of those we admire helps us create external comfort in our mental model of how the world works, and it can provide similar comfort in the stories we tell about ourselves.

If mythical figures are truly just human, what could we, as fellow humans, accomplish? Could we accomplish more if we were willing to get into the arena?

Community organizing, civil disobedience, striving for personal dreams, and other forms of living up to our own potential are uncomfortable activities compared to the allure of watching Netflix from the comfort of a couch. If we can convince ourselves that people who do “big” things are simply different than we are, we more comfortably avoid taking on the challenge ourselves.

Part of our impostor syndrome is fueled by a desire to belong, and another part is fueled by a fear of what we might have to do to be who we want to be.

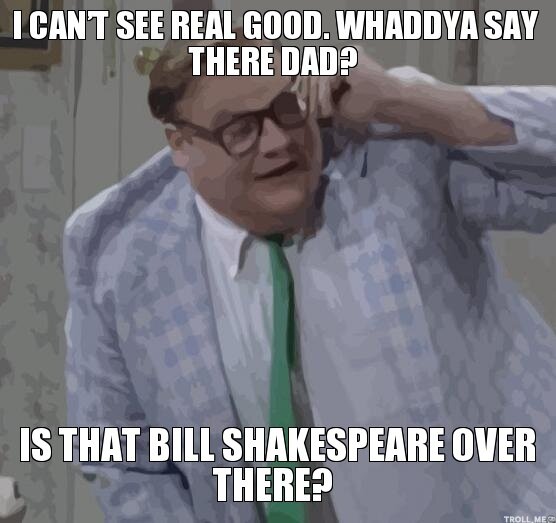

Motivational Speaker Matt Foley (Chris Farley) voicing the inner critic of comparison

Deciding that what we want is not practical is easier than finding out the hard way through trial and error. We are incentivized to keep the mythology of perfection in our heroes not only to keep external critics at bay, but to keep their powers on another level from our own, safely tucked away on an out-of-reach shelf.

What is our full potential? We know our flaws, and we can make those into excuses for why we cannot or do not deserve to “play big.”

What could we accomplish without these limiting beliefs?

The painful answer: we won’t know until we’ve done it.

“Life can only be understood backwards; but it must be lived forwards.”

Soren Kierkegaard